On a rail journey through the heart of India, Roger Norum experiences faded beauty and endless colonial charm

“There are people in the world who have seen India,” our turbaned butler, Prakash, informed us. “And there are people in the world who have not seen India. Today you are going to create history.” And with that, we were off, trundling along the 2,000-mile journey bound for New Delhi aboard a 22-carriage, private magic carpet ride of a train outfitted with two dozen attendants, eight chefs, and scores of guides, waiters and engineers. I watched as the stuffed naans, coconut burfee and mobile chaat carts of Mumbai’s elephantine railway station faded into the distance below a setting sun.

From Mumbai, the train wends its way north past the Ajanta Caves of Maharashtra through the fortress cities of Rajasthan and onto Agra and Delhi, stopping off in a destination or two each day. At Ajanta, we visited two dozen sacred caves built between the first and fifth centuries – Buddhist monastic shrines built right into the limestone, adorned with elaborate architectural carvings and towering stupas. They were accidentally happened upon in 1819 by a British officer on a hunting party and have since become one of India’s most awesome (but little-known) sights.

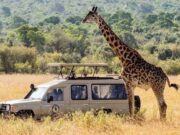

Further north, we were cart-drawn by burping, farting camels towards sundowner cocktails and a barbecue dinner served on the sand dunes in Bikaner. And north of here, we puttered around in an olive drab Jeep on the lookout for tiger in Ranthambore National Park. Home to leopards, wild boar and spotted deer, Ranthambore is also India’s top tiger reserve, set up when poaching began to threaten the country’s declining tiger population. A shame that we visited on a Sunday, though, as all the tigers had evidently taken the day off.

With its clean lines, fine rosewood panelling and polished, burgundy paint job, the Maharajas’ Express felt more like a vintage Bugatti than a rail transport vehicle. But while five-star in class and service, the train is not quite the over-the-top, opulent luxury of the mythologised Orient Express. There are no leather Louis Vuitton steamer trunks. No tuxes worn for dinner. No cigar smoking lotharios or fawning, white-gloved servants at one’s beck and call. The clientele on board was less Russian oligarch and Indian zillionaire and more well-heeled British and American couples. If this is Orientalism,

it’s at least done with some respect and humility.

Early each morning, we were served tea (for the Brits) and coffee (for the Americans), before the red carpet was (yes, literally) rolled out for us at our day’s ports of call. And the days out in the heat of India made for a glorious return to our magic red carpet. On board each night, Prakash, besuited in a gold-leafed, mandarin-collared waistcoat, prepared the Egyptian cotton beds, and the train’s soporific rocking motion sent me swiftly off to sleep. And oh, how we dined. Delhi-born, mustachioed chef du train Shanaj Madhavan (“Call me ‘John’,” he insisted) served us everything from berry compote pancakes to filet mignon and dum ka ghosht, a spicy concoction of succulent lamb cooked in an aromatic onion and cashew sauce. How he conjures up haute cuisine worthy of Michelin stardom from a kitchen the size of a broom closet – and one travelling at 60mph, no less – is anyone’s guess.

romantic and eco-friendly

Despite great distances and often-shabby infrastructure, rail travel is the best and most enjoyable way to get around India. For one, romantic and eco-friendly rail travel is the new black. With over 37,000 miles of track connecting some 7,500 stations around the country, trains become mobile picture windows from which to gaze at India in all its traditional glamour and glory, in all its raw humanity and destitution. As that master of rail intrigue Agatha Christie wrote, “To travel by train is to see nature and human beings, towns, churches and rivers, in fact, to see life.”

But it was this life – being eyewitness to India’s poverty – that became sources of consternation and discussion at dinner. Mendicants, lepers and hungry-looking children living on the side of the rails were not uncommon sights for us. How to justify spending thousands of pounds on air-conditioned mobile luxury when outside were what looked to be hungry, suffering people? It wasn’t something that sat easily. Of course, privilege – specifically the privilege of being white and British – is part of Indian history too, and perhaps the divisions between the wealthy and the poor is not something that should be glossed over or excised from the history books.

The most spectacular dioramas of Indian life we saw were the fortresses of Rajasthan. The maharajas themselves – the great kings that ruled India’s states for several hundred years – were seriously wealthy rulers who built astounding, well-fortressed cities which many of them named after themselves: Udaipur, Jodhpur, Jaipur. Today post-Raj, the maharajas maintain their fortresses and wealth, but their official power is largely symbolic. The so-called blue city of Jodhpur stood out for its sandstone Mehrangarh fortress, which looked over a series of labyrinthine medieval lanes, glimmering blue (blue once signified the home of a Brahmin, though non-Brahmins seem to have cashed in on this too).

But it was the quiet moments, the slow days aboard the train that I enjoyed most. The slow clackety-clack of the carriages hulking down the track were a sound I no longer heard in the flurry of activity in the London Tube. India is grand and incredible, as its tourist brochures remind us, but it’s also simple and plain. Travelling by train lets you see that.

marble and pearl

On our last morning, we pulled into the Taj Mahal. For the last time, our attendants rolled out the red carpet for us, and we strolled off it into the marble and pearl mausoleum which Shah Jahan built in memory of his third wife, Mumtaz, in 1648, soon after she died while giving birth to their 14th child. Standing next to the white-domed Taj, though, it wasn’t the structure’s superlative beauty, its symmetry or its ornate nature that won me over. It was the imperfections: decorative lotus motifs inlayed in jade and yellow marble which time had tarnished; Persian herringbone bas reliefs that had chipped off; a tuft of dirt swept into the corner of the mosque’s vaulted, multi-chambered octagonal suites.

Up close, stunning, picturesque India was also weathered, besmirched and fading. It had its ugly bits too. In short: it was human. This didn’t make it any less incredible.

WAY TO GO

Railbookers offers a selection of holidays with the Maharajas’ Express. Prices start at £3,099 per person for a four-night journey from Delhi to Agra and Jaipur, including a champagne breakfast overlooking the Taj Mahal and Elephant Polo in Jaipur’s Amber Palace; Tel: 020 3327 2449 / railbookers.com.