Admitting her equestrian skills are a little rusty, Emma Gregg saddles up for a riding safari in one of Southern Africa’s most beautiful wildernesses, the Okavango Delta

Once you’ve been on safari a few times, you don’t usually stop to look at an impala. But this was different. Glowing in the delicate morning sunlight, the pretty little female was so close, we could see the tiniest twitches of her nose and ears. And to make this intimate sighting extraordinary, by her side, quivering on legs as wobbly as reeds, was a calf that couldn’t have been more than an hour old.

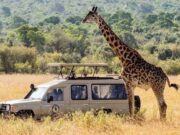

Not wanting to disturb them, we moved on – not with the roar of a four-wheel-drive engine, but with the soft crunch of hooves on dry leaves. That’s part of the magic of a riding safari. Freed from the noisy armour of a vehicle, your silhouette disguised by the shape and movement of your horse, you blend into the bush. Shy animals such as impalas, warthogs and zebras will bolt if a car comes too close, but are largely unruffled by the gentle approach of a horse and rider.

Often, they simply gaze back, as if assessing you on equal terms.

Our day had started before dawn, with a quick gulp of tea. Soon and with minimal fuss, we were in the saddle. Whether you’re driving, walking or riding, the early hours are an invigorating time to be in the bush. Every sunrise, it seems, is cause for celebration – birds call out in triumph at having made it through the night, antelopes posture and prance and wildebeest munch contentedly on the cool grass.

As riders, we felt like privileged members of this natural community, rather than mere observers. Our horses were constantly tuning and retuning to sounds, smells and movements and I, too, found my ears, eyes and nose adjusting to the subtleties of our surroundings. This was Africa, after all, and we were exploring a stretch of wilderness that was both beautiful and dangerous, patrolled by creatures that could do serious damage.Every time we passed an untidy heap of fresh-looking elephant dung or, thrillingly, spotted the rounded paw print of a lion or leopard, I remembered the advice of our guide. You must always stay alert, because you never know what might be watching you.

BACK IN THE SADDLE

Our base was Macatoo Camp, a small, dedicated riding camp run by African Horseback Safaris on the western edge of Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Its stables house around 40 horses – over four times the maximum number of guests. Most of the animals are glossy thoroughbreds, Namibian Hanoverians or Arab-Kalahari crosses, all immaculately cared for.

Well known in the tight-knit world of riding enthusiasts, Macatoo attracts serious equestrians as well as hobbyists; champions such as Mary King and Lucinda Green have led safaris here, and past guests include Prince William and Prince Harry.

Of the others in my group of six, three had more than one horse of their own back home. Describing myself as “embarrassingly rusty” in my pre-ride questionnaire, I had felt rather inadequate, but I needn’t have worried. While African Horseback Safaris don’t allow beginners to ride, they’re patient with those who need to regain their confidence, assigning them a suitably placid steed and sticking to undemanding terrain for as long as it takes.

If you find your riding legs quickly, within days you could be galloping alongside zebras or giraffes.

My horse was so gentle, a beginner would love him, I thought. But our guide was adamant that this was no place for novices. A horse is likely to react to danger before its rider has even detected there’s anything amiss, and if your horse bolts, it’s crucial that you know how to stay in control.

Ending up in a crumpled heap on the ground may be undesirable at the best of times, but could be disastrous when there are restless lions or angry elephants about. Unlike game drives, riding safaris never set out to find dangerous animals. But sometimes, dangerous animals find you.

Our morning rides lasted around four hours, time to cover far more ground than we ever could on foot. It was November and the Okavango floods had receded, leaving the landscapes superbly varied – grasslands dotted with palms or criss-crossed with shimmering channels of water, woods scattered with butterfly-shaped mopane leaves.

The gap between our morning and afternoon excursions was partly filled with a lazy brunch; occasionally, the staff would surprise us with a fully dressed table set up in the wilds. After this came an even lazier siesta-time, spent snoozing or simply mooching about the camp with a book. In the evenings, guests and hosts alike gathered around the flickering campfire to swap stories.

Macatoo does back-to-basics extremely well. It’s unfenced, immersing you in the wilderness; after dark, animals make their presence felt with a sporadic chorus of screeches and snorts. You sleep under canvas, but the tents are deliciously comfortable, with writing desks and private decks.

MEETING THE MATRIARCH

The daylight hours end with a ride that’s shorter and gentler than the morning workout. By my third afternoon, I realised I had my confidence back. Rounding some trees, we spotted a small herd of elephants, and I didn’t waver.

But then, suddenly, another group emerged from a thicket. They were far too close for comfort. In front was an indomitable-looking matriarch. One shake of its ears, and our guide gestured for us to move away at speed – but the route he indicated led straight into a water channel. Blood pumping, heart pounding, we crashed in, spray fountaining up from our horses’ hooves. Only when we were well out of danger did we slow to a wade. Too exhilarated to do anything but grin like a fool, I turned to my companions. They were all doing exactly the same.

WAY TO GO

Horseback safaris for riders of all abilities are available in beautiful wilderness regions in Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique and South Africa. They include half-day tours suitable for beginners, more demanding riding lodge-based safaris, or truly challenging mobile safaris lasting over a week, spending long hours in the saddle and fly-camping in the wilds each evening.