Most visitors to Cyprus stay on the coast, but away from the neon and the nightclubs is a world of mountain trails, dramatic gorges and sleepy wine-growing villages.

I decided I would lose myself in Cyprus. Why not? The spring sunshine was blazing and the fields were scarlet and blue with poppies and cornflowers. The roads were empty. Driving through the western foothills of the Troodos Mountains, the spine of peaks that runs across the west of the island, is pretty hit-and-miss in terms of navigation in any case, as a crossroads may point in several directions to any one village, and maps of the island tend not to agree with one another. So I turned inland from the main Limassol-Paphos road and headed hopefully for the hills.

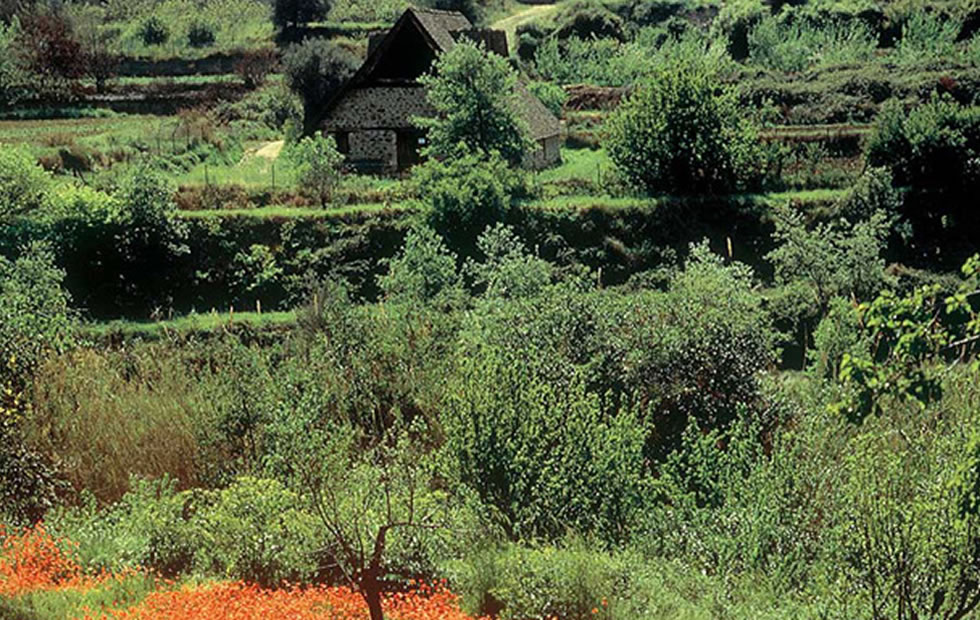

Windows wound down to let the intoxicating scent of wild herbs breeze through the car, I climbed up through wine country, regimented rows of vineyards ripening in the Eastern Mediterranean sun, other fields green with almond and apple orchards, herds of goats sheltering from the sun under the branches of ancient olive trees.

I stopped at Alassa, near the Kouris Dam, one of many reservoirs that keeps the island watered. Birds of prey wheeled overhead on the afternoon thermals. A sole fisherman, the only other human in sight, sat patiently by the water’s edge. Insects hummed in the sun. It was hard to imagine that this is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Mediterranean, receiving some two million visitors a year. Where was everybody? Not that I was complaining.

Almost reluctantly, I headed on upwards through the village of Monagri, a cluster of whitewashed houses with terracotta roofs arranged around a squat church. A couple of wineries here sell locally produced reds and Commanderia, the amber dessert wine that’s been made on the island for 4,000 years. The streets were almost deserted save a couple of old ladies in black, sitting outside their houses. We exchanged a ‘Kalispera’ (good afternoon) but they didn’t speak English and my Greek is limited to tourist phrases. Up here in the hills, it’s a different world from the hustle and bustle of the coast, where Cypriots, already proficient in English and German, are turning their hands to Russian to communicate with the newest influx of sun- and pleasure-seekers.

Onwards and upwards to Omodhos, the winegrowing capital of the Troodos, where I spent the night. Coach tours come to Omodhos laden with day trippers from the coast, here to admire the monastery, shop for souvenirs and taste the wines. But if you arrive late afternoon and stay in one of the agrotourism establishments – Stou Kir Yianni (www.omodhosvillagecottage.com) is my favourite, just three suites in an old stone house – the atmosphere gradually mellows. Finally, after sunset, the town reverts to the locals.

The next day, vaguely following the map, I headed high into the Troodos, through cool pine forests, the busy resorts of the coast shimmering in a blue heat haze, miles below. I hiked the Caledonia Trail, one of several well-marked footpaths maintained by the Cyprus Tourism Organisation. It’s an easy, two-mile woodland descent along the course of the chilly Kyros Potamos river, scrambling over mossy rocks and occasionally, balancing on stepping stones to cross the river itself. The reward at the end is a plunge into the deep pool under the Caledonia Falls, where the river gathers pace and tumbles over a jutting rock face. Further down the hill, the Psilo Dentron tavern serves freshly grilled mountain trout. This being Cyprus, famed for its hospitality and love of food, there’s usually a taverna to be found at the end of any walking trail.

SEEKING THE AUTHENTIC CYPRUS

The island is full of surprises once you leave the busy coast, which although known for its luxury hotels and spas, is another world from the quieter, more authentic Cyprus I was seeking. I love the protected Akamas Peninsula on the island’s far western tip, according to legend, the one-time hunting ground of Adonis and location of the woodland glade in which he first spotted Aphrodite bathing in a rock pool (sadly, a rather uninspiring tourist attraction nowadays). But love-struck gods and goddesses aside, Akamas reveals great natural beauty. With a friend, I walked the Avakas Gorge, initially wandering under pine, cypress and carob trees before the trail narrows into a deep, sheer-sided gorge, strewn with giant boulders that have toppled off the tops of the cliffs during the island’s various earthquakes. On the broad sweep of Lara Beach, leatherback and green sea turtles come to lay their eggs and in summer, you can help the volunteer conservationists who keep a patient vigil over the hatching eggs, putting protective cages over the sandy nests and removing exposed eggs to a hatchery. On bright nights, hundreds of newly hatched baby turtles scurry down the beach, guided by the moon, to the sea.

A much tougher hike, and one few visitors know about, is the ancient Camel Trail, an intriguing path leading from the former copper mines of the western Troodos to Paphos on the coast and named after the camels that used to bear the heavy loads. The walkable section starts in Kaminaria village and leads over rocks and through dense pine forest to Vretsia village. Along the trail are three graceful medieval stone bridges, Elaia, Kefelos and Roudias, built by the Venetians in the 15th and 16th centuries. The bridges are purely ornamental now but make great picnic spots, in the serene surroundings of the deep forest.

Again, there are numerous agrotourism houses to stay in around this area. The whole agrotourism concept is supported by the government, which gives grants to restore old stone houses for tourism and help preserve village life; like many Mediterranean destinations, Cyprus struggles to maintain its village communities as young people leave for the bright lights of the coast. There are more than 50 houses in the official agrotourism scheme and many more private ventures. Village life follows the same lazy pace wherever you go. Enjoy meze and organic wine in the local village taverna for dinner, shoot the breeze with the owner over a raki or two and fall asleep listening to the wind in the trees. We were woken every morning by a cacophony of donkeys braying and roosters crowing; rural life may be peaceful but it’s not necessarily quiet.

MOUNTAIN MONASTERIES

No visit to Cyprus is complete without visiting one of the mountain monasteries, which are spectacularly wealthy and produce their own wines and liqueurs. Kykkos, northwest of Troodos, is the richest of all and owns a precious icon painted by the apostle, Luke, which pilgrims line up to admire. But it’s the monastery itself that’s breathtaking, simply dripping with gold, beautiful paintings and lavish frescoes.

Near here, down a track signposted from the Kykkos to Stravos road, is Cedar Valley, an unusual phenomenon in that it’s the only spot on the island populated by indigenous Cyprus cedars, related to the graceful cedars of Lebanon, and a wonderfully cooling place to walk, the wind singing gently in the tall trees and all manner of bird life, including jays, who showed a healthy interest in our picnic. It’s a longish hike, 13km along the marked trail, but worth it. From the Trypylos fire lookout point at the top, 1,362 metres above sea level, you can see the peaks of the Troodos in the background and beyond the treetops in the opposite direction, the foothills stretching away in the distance. Again, not a soul in sight. I can’t think of a lovelier place to get lost.