There’s more to a Kenyan holiday than checking animals off a list, as Sue Bryant finds on a bush and beach safari

A herd of zebra is occupying the airstrip.

Not ideal when you want to land a plane. The aircraft is approaching, a tiny, white speck glinting in the brilliant blue sky over the terracotta-and-green landscape of Tsavo West, so we bump up and down the runway in our safari 4WD like lunatics, shooing away the herd.

They won’t budge. The pilot spots the action below and goes around for another attempt. He does finally manage to land, the zebra eyeing him moodily from the sidelines, but as we take off, lifting high above the vast expanse of bush, the last thing I see is the van, madly zooming up and down again, our guide still fending off the beasts.

On any safari, you learn to expect the unexpected. A large, blue lizard occupying the bikini I’d left lying around my tent? No problem. One member of our group found a small scorpion in his bathroom and another had a rock hyrax snuffling around the bed. We soon learn that this is nothing; Alex Walker, founder of the Serian Camp in the Masai Mara, was due to return to Africa from leave and the worker cleaning his house in preparation found a leopard using Alex’s wardrobe as a nest for her cubs.

open to the elements

I’ve opted for what you might call ‘rustic chic’ on my journey around Kenya. No sanitised hotels or overcrowded game parks for me; instead, four lodges that are as remote as it’s possible to be, outside the parks in conservancies – private land leased from the local tribes for tourism. I’m also approaching this journey with an open mind. I don’t want my trip to Kenya to be about checking animal sightings off a list. I want it to be about scenery, people, experiences.

Sabuk Lodge sits on a ridge in Laikipia, high above the Ewaso Nyiro river, which thunders through a gorge, hundreds of feet below. The lodge, a row of stone houses with outdoor baths and huge beds swathed in snowy mosquito nets, has no fences and animals come and go as they please.

Sleeping in a three-sided stone house with only a mosquito net between me and any nocturnal visitors takes some getting used to. On my first night, I sit out on my rocky terrace, listening to the roar of the river below, and the chirps and screeches from the bush, the sky absolutely dazzling with stars, the Milky Way cutting a glittering swathe across the heavens.

Sabuk, like all the lodges I visit, is on private land, so there are no rules about being confined to a game vehicle. The next day, we trek through the bush on camels, led by jolly Samburu guides, spotting tiny dikdiks (the smallest, daintiest antelope) scampering off into the scrub in the early morning mist. We dismount for a rest and in a small, scrubby clearing, a table has been set up, laden with toast, jam and juice, the smell of sizzling bacon wafting through the cool morning air. Our first bush breakfast.

the bare necessities

After a long swim in the river, we visit a local school, where children in immaculate uniforms study with the absolute barest minimum of resources. Joseph, a volunteer, explains that nine teachers manage 513 children, and five of those teachers are volunteers. The kids are all ages; traditionally, the first-born son of a family helps with the goats and cattle and attends school at a much later age than his siblings, so it’s not unusual to see a 16-year-old warrior in the first grade. “Sometimes the children can’t get to school,” explains Joseph. “Some of them walk 12km each way and there may be heavy rain, or wild animals. Recently there was a big elephant in the village.” I’m humbled by the lack of resources with which Joseph manages; bare classrooms, old books and none of the luxuries enjoyed by my own children in London. We show some of the village children the art of the ‘selfie’ on our phones, and they shriek with laughter.

Leaving this beautiful place is difficult but the plains of the Masai Mara beckon. Not the main game park, but like Sabuk, a conservancy, whereby our camp, Serian, is outside the park in a huge area leased from the local Masai. Game, of course, knows no boundaries and our luxurious tents, strung out along the bank of the Mara River, are visited throughout the night (as we can tell by the tracks the following morning) by hippos, warthog, impala, zebra and mongoose. Big cats are not unknown, we’re told the next day, particularly that friendly, wardrobe-dwelling leopard.

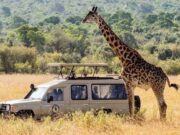

The game viewing in both the park itself and the conservancy is astonishing. We spot herds of zebra and wildebeest, dozens of antelopes, elephants, buffalo… but the highlight is, of course, the cats. Denis, our Masai guide, drives us to a rocky outcrop favoured by a pride of 17 lions and we’re not disappointed; mothers and cubs are moving languidly along the hilltop in the afternoon sun, flopping down on the occasional hillock to survey the horizon. They hardly look like killers.

Suddenly, one female is on her feet, ears pricked, moving stealthily away from the pride. Another joins her and the lions form a wide semicircle around a small herd of zebra grazing obliviously in the distance. In a flash, it’s all action. The herd breaks into a thundering gallop, dust billowing, as a streak of tan flies across the savannah in hot pursuit. She gives up but a young male leaps into action, sprinting alongside the zebra, trying to pick his moment to pounce. He’s in training, as it were, and falls back, but our pulses are racing. “He’s not ready,” explains Denis. “One kick from a zebra will kill him.”

hopeless plight

We have another zebra encounter in Tsavo West Conservancy. A tiny foal is standing in the road and won’t budge. She shies away when Richard, our guide, approaches her but follows him when he turns around to leave. Her umbilical cord is still attached and Richard decides she must be less than a week old, her mother probably killed by a lion. He persuades her to drink and we all gather round, patting her. It’s an amazing moment, although horribly poignant. “If the lions and hyenas don’t get her, dehydration will,” Richard explains. “We’ve given her the best possible chance now. We’ve rehydrated her and covered her in human scent, so at least nothing will touch her tonight.” We move on with heavy hearts and I think how anxious we all were yesterday to witness a kill – yet how moved we are today about the hopeless plight of one tiny animal, among thousands.

Because of the zebra, we’re late arriving at Kipalo, our next lodge. The Toyota bumps up a steep hill in darkness, acacia thorns snapping through the open sides, the headlights illuminating the occasional fleeing antelope. We have no idea where we are, although a small, floodlit pool and an iced gin and tonic are the perfect remedy to a long day’s travelling. But nothing prepares me for the view the following morning when I unzip my tent. I’m perched high up on an escarpment, miles and miles of bush stretching out as far as the eye can see, punctuated only by jagged red mountains. Breathtaking.

We visit the conservancy HQ – a group of tents clustered around a vast baobab tree, manned by a small group of rangers, between them trying to carry out the impossible task of patrolling 12,000 acres of bush in search of poachers. These guys are tough; part of the recruitment process is running several miles at midday wearing a backpack full of rocks. And they need to be; gruesome tools of the poachers’ trade lie around the camp, not least endless ugly coils of wire snares. Yet as Richard explains, it’s not poaching, but agriculture that poses the biggest threat to Kenya’s wildlife. “In Africa, if it doesn’t make money, it won’t survive,” he says. “At the moment, we pay the local tribes more for the land in the conservancy than the wheat farmers do but if the price of wheat goes up, it’ll be a different story.”

fragile ecosystem

Delta Dunes, our final lodge, perched in sand dunes thousands of years old in the vast wilderness of the Tana River Delta north of Malindi, has its own story of a struggle for survival. Here, environmentalists have fought a bitter battle against a Canadian company that wanted to plant thousands of hectares of biofuel plants in the delta, which has an astonishing concentration of wildlife. The biofuel company has backed off, for now, but there’s a constant sense of how fragile both the ecosystem and the economy are here.

My room up in the dunes is open to the elements, made of thatch, stone and wood and wrapped around a huge tree. The hot sun wakes me up early and I bounce down the soft, sandy path to a staggering 70km of empty beach. I share the trail with tracks of civet cat, genet and baboon and encounter the baboon troop digging in the sand for crabs along the beach. They’re my only company and the sense of space is invigorating.

Later that day, we try sand yachting – go-karting with a sail, at great speeds across the sand, and totally addictive. I calm down by paddling a kayak slowly through the backwaters of the delta, watching black and white kingfishers diving, overlooked by egrets perched on spindly legs in the mangroves.

Night falls and we lounge on giant cushions around a beach bonfire, drinking gin and tonics and later, tucking into a magnificent curry buffet. We feed bits of banana to George, a semi-tame bush baby, all soft fur and huge eyes, who inhabits a tree in the bar.

None of us wants to leave Kenya. We haven’t witnessed a kill, or seen a rhino, or a cheetah, but encounters with both humans and animals in this vastly complex country have been both moving and unforgettable.

What to pack for a Kenyan safari

• A soft-sided bag or case if you’re taking internal flights on light aircraft

• Long trousers in neutral colours

• Shorts for hot days

• Long-sleeved tops in neutral colours (for sun protection by day and mosquito protection by night)

• A fleece for evenings

• Comfortable, lightweight clothes for dinner – nobody dresses up

• Lightweight walking boots

• A hat with ties – you’ll spend time standing in your 4WD and hats can easily blow off

• Swimwear – some lodges have pools

• A strong sun block – the once-a-day brands like P20 are good

• Mosquito repellent

• Malaria pills

• Cleaning hand wipes

• Large capacity memory card

• Camera cleaning kit – everything gets dusty

• Binoculars –most game vehicles do carry some but you may have to share

• US dollars in small denominations ($1, $5 and $10) for camp tips (or you can use Kenyan shillings)

• US$50 for your entry visa

• Pencils and school equipment – see packforapurpose.com

What not to pack…

• Plug adaptors if you’re from the UK – Kenya uses the same as Britain

• High heels

• Too many items in white – they’ll get covered in red dust

• A torch – solar-powered torches are supplied in the lodges